Chinua Achebe's "Chike and the River" (Random House) reminds me of a of a folk tale, even though it's set in the modern world. It was first published in 1966, eight years after the author's pivotal novel "Things Fall Apart." It is the first of his four children's books and is the story of a curious boy named Chike who yearns to cross the Niger River. Why? Just to see what's on the other side.

As his mother's only son, Chike is sent away from their bush village to school, where he lives with his uncle in a house crowded with tenants. "In Umuofia," Achebe writes, "every thief was known, but here even people who lived under the same roof were strangers to one another. Hiss uncle's servant told Chike that sometimes a man died in one room and his neighbor in the next room would be playing his gramophone. It was all very strange."

All the requisite English traditions are in evidence at Chike's school. Football (soccer), cramming for exams and English food are part of his school life. The boys are told such things as, all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy. A ridiculous thing to say in a society where children fetch water at dawn.

This is a young adult book that, at every page turn, tugs at the notion of tradition versus modernity. It describes the Africa of today with precision.

As his mother's only son, Chike is sent away from their bush village to school, where he lives with his uncle in a house crowded with tenants. "In Umuofia," Achebe writes, "every thief was known, but here even people who lived under the same roof were strangers to one another. Hiss uncle's servant told Chike that sometimes a man died in one room and his neighbor in the next room would be playing his gramophone. It was all very strange."

All the requisite English traditions are in evidence at Chike's school. Football (soccer), cramming for exams and English food are part of his school life. The boys are told such things as, all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy. A ridiculous thing to say in a society where children fetch water at dawn.

This is a young adult book that, at every page turn, tugs at the notion of tradition versus modernity. It describes the Africa of today with precision.

I've seen for myself, in the Rift Valley in Northern Kenya (a different area but connected to the struggle of past and present), this clash of new and old. There, herders who have no electricity, cars or modern medicine, wear Micky Mouse tee shirts and have modern wrist watches. They, indeed, are living on a bridge of time, and I've often wondered what that must be like. This coming of age story, on so many levels, addresses that reality in a profound way.

I've seen for myself, in the Rift Valley in Northern Kenya (a different area but connected to the struggle of past and present), this clash of new and old. There, herders who have no electricity, cars or modern medicine, wear Micky Mouse tee shirts and have modern wrist watches. They, indeed, are living on a bridge of time, and I've often wondered what that must be like. This coming of age story, on so many levels, addresses that reality in a profound way.

The dolphin has amazed us with its intelligence. Now it turns out that it routinely defies death. It can ignore a wound that would kill a human within hours. Dolphins, according to a new study, are frequently attacked by sharks that leave gaping holes bigger than a basketball.

"Why don't they bleed to death?" asks Michael Zasloff, professor of surgery and immunology at Georgetown University Medical Center. "Why don't they get infections? Why aren't they eaten after the injury? Why doesn't the shark finish the job?" Zasloff thinks he may have at least partial answers to those questions, although much more research needs to be done.

"I have concluded that what we see when we look at the dolphin is a medical miracle," he said. "And if scientists can figure out exactly how the dolphin cheats death, maybe humans can eventually learn how to do it too, through better treatment of all sorts of injuries, not just shark bites. "

"Why don't they bleed to death?" asks Michael Zasloff, professor of surgery and immunology at Georgetown University Medical Center. "Why don't they get infections? Why aren't they eaten after the injury? Why doesn't the shark finish the job?" Zasloff thinks he may have at least partial answers to those questions, although much more research needs to be done.

"I have concluded that what we see when we look at the dolphin is a medical miracle," he said. "And if scientists can figure out exactly how the dolphin cheats death, maybe humans can eventually learn how to do it too, through better treatment of all sorts of injuries, not just shark bites. "

Zasloff is a surgeon, not a dolphin expert, but his interest in this sea-going mammal began nine years ago, when he was visiting a marine lab in Scotland. He was told that 70 to 80 percent of the dolphins that swim in the waters near Australia have shark bites.

"When I heard that I was taken aback," he said. "How in the heck does a mammal, like you and me, survive a shark bite in the ocean, unattended, with no antibiotics?"

A shark bite involves more than just ripping out a large chunk of flesh. The shark leaves "the worst collection of toxic organisms" in the wound, so infection should follow. A human being would die of infection and shock within two or three days if not hospitalized. So how does a dolphin heal itself without medical treatment?

Zasloff is a surgeon, not a dolphin expert, but his interest in this sea-going mammal began nine years ago, when he was visiting a marine lab in Scotland. He was told that 70 to 80 percent of the dolphins that swim in the waters near Australia have shark bites.

"When I heard that I was taken aback," he said. "How in the heck does a mammal, like you and me, survive a shark bite in the ocean, unattended, with no antibiotics?"

A shark bite involves more than just ripping out a large chunk of flesh. The shark leaves "the worst collection of toxic organisms" in the wound, so infection should follow. A human being would die of infection and shock within two or three days if not hospitalized. So how does a dolphin heal itself without medical treatment?

That question haunted Zasloff for nine years, but a few months ago, he began working with Australians who are in constant contact with bottlenose dolphins, including Trevor Hassard, director of the Tangalooma Wild Dolphin Resort on Moreton Island. The resort is different from most aquatic parks in that the dolphins are free to visit, where they get an easy meal, or leave and return to the wild whenever they so desire.

Over the years Hassard and others who care for wild dolphins have seen hundreds of dolphins that have been attacked by sharks. If the attack was recent, an open wound, usually on the backside of the dolphin, seemed to have little effect on the animal. It swam normally, did not show any sign of pain -- though dolphins clearly can experience pain -- and acted as though nothing was wrong. And within about 30 days the wound was gone. There were no scars. No signs of the injury. Even the natural contour of the body was back to its normal shape. So the dolphin doesn't just recover from the attack. It regenerates the blubber and refills the hole!

That question haunted Zasloff for nine years, but a few months ago, he began working with Australians who are in constant contact with bottlenose dolphins, including Trevor Hassard, director of the Tangalooma Wild Dolphin Resort on Moreton Island. The resort is different from most aquatic parks in that the dolphins are free to visit, where they get an easy meal, or leave and return to the wild whenever they so desire.

Over the years Hassard and others who care for wild dolphins have seen hundreds of dolphins that have been attacked by sharks. If the attack was recent, an open wound, usually on the backside of the dolphin, seemed to have little effect on the animal. It swam normally, did not show any sign of pain -- though dolphins clearly can experience pain -- and acted as though nothing was wrong. And within about 30 days the wound was gone. There were no scars. No signs of the injury. Even the natural contour of the body was back to its normal shape. So the dolphin doesn't just recover from the attack. It regenerates the blubber and refills the hole!

Zasloff theorizes --just a theory at this point -- that the injured dolphin can produce stem cells that can morph into whatever is needed to fill in the wound. Perhaps, he speculated, it has some sort of a growth hormone that stimulates the production of stem cells, and maybe that same hormone would work for other mammals, including humans.

Zasloff theorizes --just a theory at this point -- that the injured dolphin can produce stem cells that can morph into whatever is needed to fill in the wound. Perhaps, he speculated, it has some sort of a growth hormone that stimulates the production of stem cells, and maybe that same hormone would work for other mammals, including humans. During that month-long healing process, the dolphin is exposed to all sorts of pathogens that should cause potentially fatal infections, but that doesn't happen. Perhaps, he suggested, the dolphin carries its own packet of antibiotics.

There is a lot of research on the composition of the blubber, and it includes "compounds that look a lot like the antibiotics that other sea creatures have to protect themselves," like algae and plankton, Zasloff said.

Maybe when the dolphin consumes those other creatures, it doesn't metabolize the natural "antibiotics" and return them to the sea. It could be that it stores those vital compounds and deploys them to an injury inflicted by a shark.

During that month-long healing process, the dolphin is exposed to all sorts of pathogens that should cause potentially fatal infections, but that doesn't happen. Perhaps, he suggested, the dolphin carries its own packet of antibiotics.

There is a lot of research on the composition of the blubber, and it includes "compounds that look a lot like the antibiotics that other sea creatures have to protect themselves," like algae and plankton, Zasloff said.

Maybe when the dolphin consumes those other creatures, it doesn't metabolize the natural "antibiotics" and return them to the sea. It could be that it stores those vital compounds and deploys them to an injury inflicted by a shark.

"It's not breaking them down," Zasloff said. "It's storing them in the blubber. It's as if the dolphin has decided to keep the good stuff that is made in the ocean by other creatures to fight bacteria." But what about the pain? The Australian caregivers say dolphins attacked by sharks don't act as if they are in pain at all.

Zasloff theorizes -- and this is just theory at this point -- that the injured dolphin can produce stem cells that can morph into whatever is needed to fill in the wound. Perhaps, he speculated, it has some sort of a growth hormone that stimulates the production of stem cells, and maybe that same hormone would work for other mammals, including humans. A lab with access to injured dolphins should be able to isolate the hormone, if it's there, he said.

"It's not breaking them down," Zasloff said. "It's storing them in the blubber. It's as if the dolphin has decided to keep the good stuff that is made in the ocean by other creatures to fight bacteria." But what about the pain? The Australian caregivers say dolphins attacked by sharks don't act as if they are in pain at all.

Zasloff theorizes -- and this is just theory at this point -- that the injured dolphin can produce stem cells that can morph into whatever is needed to fill in the wound. Perhaps, he speculated, it has some sort of a growth hormone that stimulates the production of stem cells, and maybe that same hormone would work for other mammals, including humans. A lab with access to injured dolphins should be able to isolate the hormone, if it's there, he said.

There is a lot of research on the composition of the blubber, and it includes "compounds that look a lot like the antibiotics that other sea creatures have to protect themselves," like algae and plankton, Zasloff said He suspects the animal not only carries antibiotics -- it also comes equipped with built-in painkiller.

"I propose that the wound itself is releasing a pain-relieving substance, and it must be unbelievably powerful. It has to be activated at the site of the wound, and it is not going to be addictive. I would say that is perhaps the most miraculous of all," he said. It carries its own anesthesia? "I would call it morphine," he added. "I think we'll find it in the tissue."

There is a lot of research on the composition of the blubber, and it includes "compounds that look a lot like the antibiotics that other sea creatures have to protect themselves," like algae and plankton, Zasloff said He suspects the animal not only carries antibiotics -- it also comes equipped with built-in painkiller.

"I propose that the wound itself is releasing a pain-relieving substance, and it must be unbelievably powerful. It has to be activated at the site of the wound, and it is not going to be addictive. I would say that is perhaps the most miraculous of all," he said. It carries its own anesthesia? "I would call it morphine," he added. "I think we'll find it in the tissue."

But that leaves us with a final question. Why didn't the animal bleed to death in the minutes after the attack? "That's the easy one," Zasloff said.

The dolphin probably goes into a deep dive right after the initial attack in an effort to escape, and during the dive it will need all its available blood to pump oxygen to the brain. So it shuts off the blood flow to much of the rest of its body, including the wound.

By the time the animal surfaces -- maybe 20 minutes or so later -- the small amount of blood in the wound would have coagulated, closing down any possible bleeding. It will be a while before we know if he's right. If so, the dolphin is much more fascinating that we ever imagined.

But that leaves us with a final question. Why didn't the animal bleed to death in the minutes after the attack? "That's the easy one," Zasloff said.

The dolphin probably goes into a deep dive right after the initial attack in an effort to escape, and during the dive it will need all its available blood to pump oxygen to the brain. So it shuts off the blood flow to much of the rest of its body, including the wound.

By the time the animal surfaces -- maybe 20 minutes or so later -- the small amount of blood in the wound would have coagulated, closing down any possible bleeding. It will be a while before we know if he's right. If so, the dolphin is much more fascinating that we ever imagined.

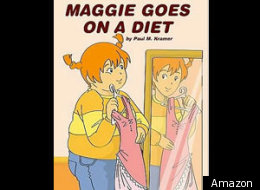

Have you seen this book advertised or discussed in articles and blogs yet? It's the one with the conundrum following it like the tailwind of a Sahara sandstorm.

An overweight young girl with braids, stands in front of the mirror holding up a too-small pink dress and sees a new and improved version of herself. The girl looking back at her is thin.

This book that many find disturbing at best and harmful at worst, will be in bookstores on October 16. It was written and self-published by Paul M. Kramer.

Amazon recommends the book for children beginning at age six. The beginning grade recommendation is First Grade. The Amazon description reads:

An overweight young girl with braids, stands in front of the mirror holding up a too-small pink dress and sees a new and improved version of herself. The girl looking back at her is thin.

This book that many find disturbing at best and harmful at worst, will be in bookstores on October 16. It was written and self-published by Paul M. Kramer.

Amazon recommends the book for children beginning at age six. The beginning grade recommendation is First Grade. The Amazon description reads:

"This book is about a 14 year old girl who goes on a diet and is transformed from being extremely overweight and insecure to a normal sized girl who becomes the school soccer star. Through time, exercise and hard work, Maggie becomes more and more confident and develops a positive self image.

Teaching kids to make healthy lifestyle choices from an early age is a worthy endeavor. And childhood obesity is a serious public health issue nationwide. According to the CDC, approximately 17% of children in the US are overweight. This is over triple the rate a generation ago.

But Maggie isn't dreaming of being a soccer star. This little girl is driven to get into the pink dress. The book is selling skinny first with everything else to follow.

Just as childhood obesity is on the rise, eating disorder rates are climbing alarmingly and are affecting younger and younger kids. Last year, the American Academy of Pediatrics reported a 199% increase in the number of eating disorder-related hospitalizations for children under the age of 12.

Whether the book sells well or is effective in its message, remains to be seen. This blogger, though, will leave her readers with one notion. The emphasis is misguided from the beginning of the book. Children are not the ones to be targeted and certainly not children as young as six! It is, in fact, parents who need to be educated and become proactive about this national epidemic. Only then will there be any hope of eliminating such an emotionally wrenching and potentially life shortening problem.

Teaching kids to make healthy lifestyle choices from an early age is a worthy endeavor. And childhood obesity is a serious public health issue nationwide. According to the CDC, approximately 17% of children in the US are overweight. This is over triple the rate a generation ago.

But Maggie isn't dreaming of being a soccer star. This little girl is driven to get into the pink dress. The book is selling skinny first with everything else to follow.

Just as childhood obesity is on the rise, eating disorder rates are climbing alarmingly and are affecting younger and younger kids. Last year, the American Academy of Pediatrics reported a 199% increase in the number of eating disorder-related hospitalizations for children under the age of 12.

Whether the book sells well or is effective in its message, remains to be seen. This blogger, though, will leave her readers with one notion. The emphasis is misguided from the beginning of the book. Children are not the ones to be targeted and certainly not children as young as six! It is, in fact, parents who need to be educated and become proactive about this national epidemic. Only then will there be any hope of eliminating such an emotionally wrenching and potentially life shortening problem.